Arlis Alikaj reported from Albania

Amra Avdić reported from Bosnia and Herzegovina

Jeta Selmanaj reported from Kosovo

According to the International Labour Organisation, Covid-19 impacted Balkan young people disproportionately, causing unemployment, poor education, and mental health issues that may last beyond the pandemic. This raises deep concerns given that, even before the pandemic, young people in the Western Balkans were already facing significant challenges concerning employment and social inclusion. But is it too late to avoid a ‘pandemic scar’ on youth? What are the solutions for youth-inclusive recovery?

One day after Albanian Liberation Day, which is an annual public holiday the night of November 29th, 2020, was a scary night for the citizens of the Albanian small town of Librazhd. A young man jumped from the 5th floor of a building, attempting to end his life. The horrible noise and his screams shocked the neighbours. The young man was transported urgently to the local hospital; because of multiple wounds, he had to be transported to the Trauma hospital in Tirana. The 24-year-old with the initials J.S., fell on a decorative bush in front of the building, which saved his life but left him paralysed for his entire life. The city of Librazhd had never experienced this. The neighbours gathered immediately wondering why he might have done this. Lushka, a middle-aged woman from Librazhd, was screaming why did he do this. She said there was no reason for a boy to end his life.

Although in every local and national media this was reported as an attempted suicide, the police officially filed it as an accident. There were two different versions of the story. We talked to his family. His father wasn’t feeling comfortable because of the police report. He was feeling bad at that time and reported it as an accident because of the cultural and public opinion pressure.

As if poverty wasn’t enough, the silence and sorrow had plagued the family. The television was off because the family couldn’t stand any sounds.

We found the young boy paralysed, lying in his orthopaedic bed, unable to talk much. He still feels a lot of pain. Immediately after he saw somebody had come to interview him, he burst into tears. ‘At least I am alive’ – he said. We asked him how he was and what happened that night.

”I wasn’t feeling OKAY when I did this. I had my own personal problems and crises. I couldn’t open myself to anyone because they would all call me crazy. I was mentally ill and loaded with negative energy. I am the enemy of myself. After I did this, everyone tried to listen to me, but now it is too late,” – the young man ended the conversation.

We respected the family’s privacy. He wasn’t feeling comfortable continuing the conversation so his father bumped in.

I want my son’s case to be a message to raise awareness and to feel others’ pain. That makes us human. We made a huge mistake, which my other son let me know. We shouldn’t have reported the situation as an accident. We are not ashamed anymore to say our son was mentally ill from the quarantine. He broke up with his girlfriend, failed the university exams, and sat 24 hours staring at the wall; it was a moment of weakness for him. I feel bad as a father. I should have stayed closer to him and paid attention even to his weird attitude. I should have done a better job telling him that failing is okay. I regret my mistake. Even we as parents learn from our own mistakes.

This poor family has to overcome prejudices and small talk after this happened. The survivor can’t go outside because he has lost both his legs. His vertebral column is broken, leaving him disabled for the rest of his life. As this was not enough his parents had to deal with the curiosity and rude questions from the community and neighbourhood. All Nazmi, the father of the youngster, has to say for them is not to gossip about his tragedy but watch your children and try to stay close to them.

Arjana Novaku, an unemployed woman who has a disabled husband at home, talks about the aggravated situation that the pandemic has created in her.

Pictured: Arjana Novaku

“The pandemic has been very difficult for my family and for me as a woman, alone, unemployed. It has been very stressful to face the economic crisis and this aggravated me as I have to take care of a person with disabilities as well.

I could not do it, as I am also chronically ill. This stress has also affected my infant children. I cannot fulfil their needs.

I am the breadwinner. I have made numerous requests for help, I have received only empty words, no support. I am tired of coming around in local institutions, hoping that I will find a solution, but it has been impossible,” Arjana concludes.

One of her daughters attempted suicide during COVID-19. She had suicidal thoughts and said she wasn’t happy in this life.

Her classmates were constantly bullying her about her weight. She received a lot of memes tagging her. It was a miracle I caught this early enough; I talked to the parents of those bullies and the teacher. They were aware of my concern and immediately took action to educate their children better and apologise. I remember one of the bullies even cried when he learned how deeply his attitude and their nasty words affected my daughter.

Self-Harming Among Teens on the Rise

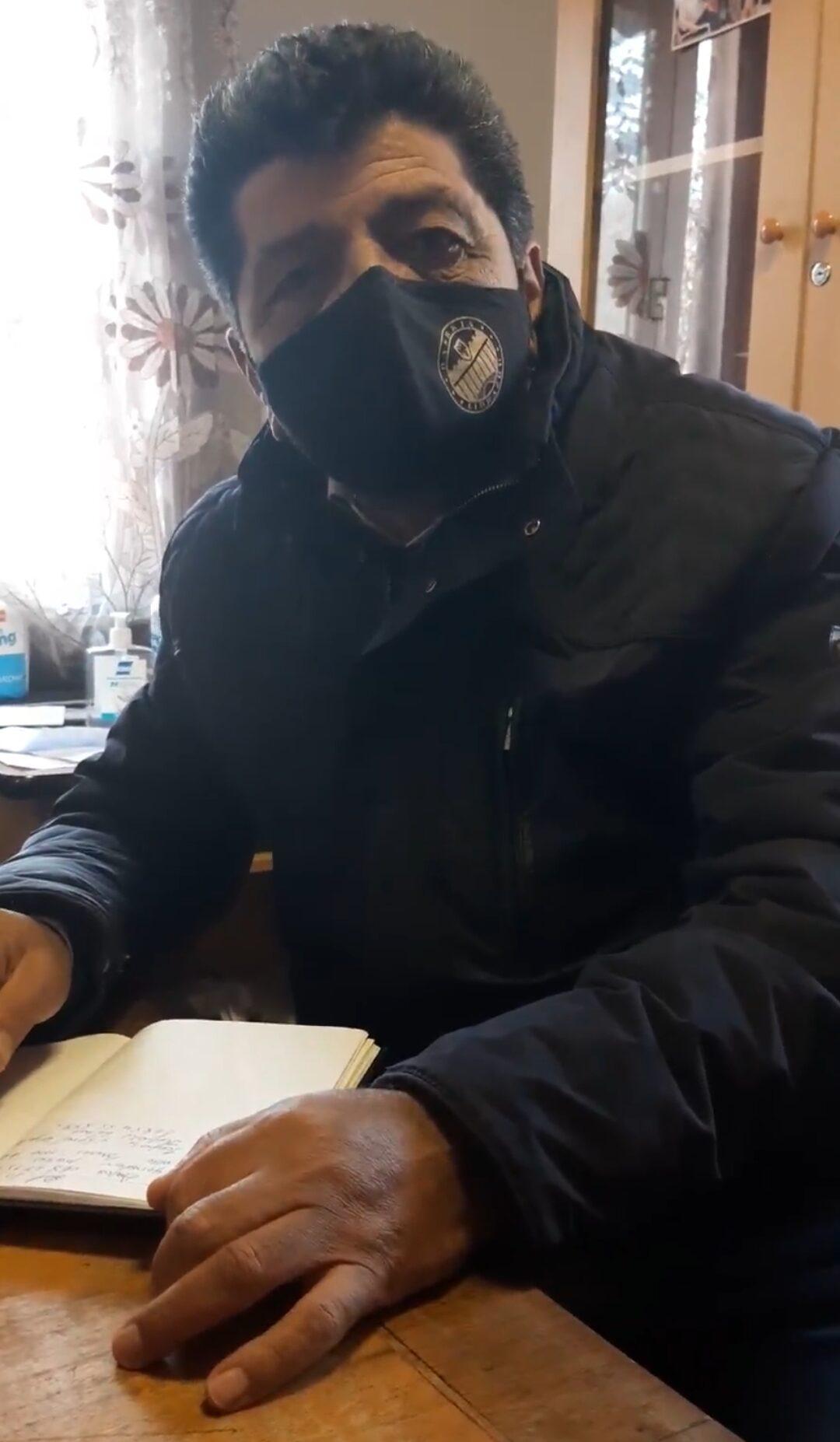

Rexhep Shaka, a social worker at the Librazhd municipality, says that Albanian rural areas are left behind other priorities. ”We do not have capacities and funds. I can listen and we have always tried to stay close to their needs but more psychologists and psychiatrists are needed to handle the issues. Some of the youngsters felt really alone in the world. Typical actions include cutting, scratching, and picking or pulling skin or hair. Some people may also bang their heads against the wall or punch objects or themselves. However, not all self-harming is suicide-related. Breaking free of self-harm can take years; seeking out a mental health professional can help adolescents move from self-harm to self-care. But not everyone will be ready to stop right away, which is something that parents need to keep in mind.”

Pictured: Social worker of Librazhd city, Rexhep Shaka

Miljana Hasanaj, a psychologist from ECSR (Environmental Centre For Studies and Research) sees solutions about the youth mental illness in nature rather than the traditional curricula. ”I always tell youth who struggle with things in life, go out in nature, it will never fail you. Nature provides great stress relief by enabling us to remove ourselves from the things that cause us stress in the first place. The Ministry of Education and Sports in Albania should emphasise the role of psychology in schools. Ideally, each school should have a psychologist. More funds should be allocated towards employing psychologists. Sometimes a voice to listen to is all they need.”

The team of journalists from the Young Journalists Competition. From right to left: Amra, Jeta, and Arlis.

The team of journalists from the Young Journalists Competition. From right to left: Amra, Jeta, and Arlis.

Different countries, same problems

If we drive a little more than 400 kilometres to the north-west, to Bosnia and Herzegovina, we will understand why this is a problem that affects the Western Balkans intensely, and that in this case there are no big “differences” between the countries of the region.

Nihad Bojić from Šerići, BiH, recalls the painful moments when he found out how his friend committed suicide, telling us how much of a misconception it is that suicide should not be discussed because it is then encouraged.

“I found out about that horrifying news from his neighbours. It was truly one of the hardest calls, to find out that a loved one left this world in such a way is devastating.”

“I found out about that horrifying news from his neighbours. It was truly one of the hardest calls, to find out that a loved one left this world in such a way is devastating.”

60 people close to the person will be affected by his / her suicide

The suicide rate in BiH according to the World Population Review is 10.9 per 100,000 inhabitants. Why we must take cases of suicide seriously and systematically is shown by the scientifically proven fact shared with us by Vildana Zrnanović-Hasanović, MSc. in psychology. She says that behind every person who commits suicide an average of 60 people close to him/her are “affected” by this death.

How exactly this affects family and friends, Zrnanović-Hasanović answers, “Although many sympathise with family members and friends of the person who committed suicide, they are often both stigmatised and isolated. Stigmatisation refers to the attitude of their environment that the victim and her family and loved ones did not provide support and could not cope with emotional problems, and the feeling of stigma and shame is a barrier to their seeking support and help from professionals.”

Also, Zrnanović-Hasanović confirms that family and friends are often at high risk of suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts:

“A study conducted by Pitman (2016), which examined 3,432 young people who lost a close friend or family member due to suicide, showed that they are more likely to attempt suicide than people who lost a close person due to some other natural cause. The effect is the same regardless of whether they were family or friends to the victim.”

Fortunately, within Bojić’s circle of friends, the need for meaningful conversations and mutual support after the loss of their friend is emphasised.

“We talk more intensely about what concerns everyone individually. Everyone carries their own cross and helping someone to bear the burden of the cross more easily is the most primordial expression of humanity as such,” ends Nihad.

Back to school with post-pandemic measures.

Faced with the loss of one of her students in the middle of this year, Dr. Omerdić, PhD. at the Faculty of Law, University of Tuzla, is working intensely to bring changes within the system, in which she operates.

“Students with whom I had the opportunity to hang out before the pandemic, who attended in-class lectures when I see them after a while, certain changes can be noticed.”

Should professors react in case of a noticeable change in the mental state of their students? Prof. Omerdić explains, “Privacy and the right to family life should always be protected, but at the same time, there is an obligation to react in some way if you know that there are certain behaviours and actions contrary to applicable norms.” How important it is to work in the field of mental health for the benefit of the student within the academic community and how Prof. Omerdić sees changes in students during a pandemic listen in the video below.

Interview with Dr. DŽENETA OMERDIĆ, PhD

Call “The Lifeline,” someone will always listen.

In the absence of a systemic solution in Albania and Bosnia and Hercegovina that would contribute to the prevention of suicide among young people, one example from Kosovo still gives hope.

When the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, a call centre was established for young people who were struggling mentally. ”Sometimes, all we need to do is to break the silence in order to understand how much our story relates to others. For the one that feels alone! For the one that feels powerless! And the one that is tired! You are not alone! Together we heal. Just talk and break the silence, call ”Linja Jetës” and open the windows of your depression at 0800 12345.” This is a powerful message, which was spread by one of the famous pop stars in Kosovo in her YouTube video with 29 million views. The campaign was spread massively amongst famous people and was a great success.

There is hope.

This call centre has helped people who have telephoned and shared their own problems and had suicidal thoughts. On the other end of the phone line are well-trained professionals supervised by a psychologist, who listens to them unconditionally, without revealing the identity of the caller.

The director of this S.O.S. call centre, Bind Skeja, said for the Young Journalist Initiative, based on a research of calls, the pandemic had seriously affected the health of young Kosovars but not only them. Skeja shows that since this line was opened, almost no day passes without calls.

Pictured above, Bind Skeja, director of the “Linja e Jetës” call centre

”It rarely happens to not have any calls. We have 4 – 10 calls per day. We guarantee them anonymity so we gain their trust. We are extremely careful when it comes to our image. We have been working for almost two years to gain public trust. It is constant work because it is still a struggle with the stigma that these people experience.”

Since Skeja is a psychologist, he has an opinion about the impact of the pandemic, especially on young people. It created a huge gap and it will be difficult to fill it over time, especially for those people who were already closed within themselves. In Kosovo, it is a problem because we do not have research that reflects this, but it is a call for 2022 to start raising the awareness of institutions more, to invest in activities, awareness, and training on mental health, continues Skeja.

He condemns Kosovar institutions for not having taken the issue of mental health seriously. ”This issue was not taken seriously after the pandemic or before, starting from the lack of psychologists in schools. The Mental Health Centre in Prishtina is overloaded, there is no psychologist in the Family Medicine Centres. Investments are very low, and only 3% of the state health budget goes to mental health, ends the director of Linja e Jetës.

Youth supporting youth

Those who speak directly to the callers are volunteers, and one of them is Lirigzona Rrustemi for whom this work is very important. This is her story:

Lirigzona’s interview video.

The statistics Kosovo Police provided to us show that the numbers of suicides and suicide attempts were higher in 2020 and 2021 compared to previous years.

| Year | Number of suicide attempts | Number of committed suicides |

| 2019 | 101 | 31 |

| 2020 | 111 | 40 |

| 2021 | 142 | 34 |

For the director of the Association of Psychologists of Kosovo, Naim Telaku, the pandemic and all problems that came with it may have led people to think of suicide.

Pictured, Naim Telaku, president of the Association of Psychologists of Kosovo during the interview with journalist Jeta.

Telaku says that for many reasons, the pandemic has affected the mental health of young people now, and this will have consequences in the future as well.

The youth was one of the most vulnerable target groups affected by the pandemic.

”The Covid-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on the mental health of the population as a whole, but some groups, in particular, were harmed more. In young people, in addition to the mentioned effects, troubles of obsessive nature have been observed, followed by an increase in the amount of food, alcohol, and drugs consumed as a function to manage high levels of stress. For young people who are part of the education process, the pandemic has many negative effects indirectly due to detachment from the education process. These effects can be long-term, which can be combined with the negative effects of preventive and isolation measures and harm the mental health of young people for the upcoming several years.”

The end of the pandemic may now be in sight. But its effects on young people will last well beyond it. Gaps in the response of institutions and national governments demonstrate that further policy measures are now needed to address the long-term consequences of the pandemic on young people’s education, work, and mental health. The three areas of education loss, economic loss, and poor mental health now form a long-term ‘pandemic scar’ on young people. This may follow young people for the rest of their lives and requires governments and institutions to act today to deliver a youth-inclusive recovery, says a report from European Youth Forum.

If you are a youth struggling right now, feel free to call these numbers. Someone will be there to listen.

Albania – The Albanian National Child Helpline, 116 111

Bosnia and Herzegovina – “Vive žene”, +387 35 226 819

Kosovo – Linja e Jetës, Call Centre for Suicide Prevention, 0800 12345

This story was developed through the Media For all programme funded by the UK Government. The content gathered and views expressed are the sole responsibility of the author