Author: Arlis Alikaj

The city of Pogradec is located on the western shore of Lake Ohrid, which is the heart and soul of this city. Pogradec is not the only one that recognizes the value of this beautiful lake. In 1980, UNESCO declared it a Natural Heritage Site, and since 2019, the Albanian part has also been included on the list. Ohrid is the deepest lake (285 meters) in the Balkans and is divided between North Macedonia (in Ohrid and Struga) and Albania.

It took about 4 million years for this lake to take its current shape, starting from the moment when the land began to shift on the western side of the Dinaric Alps. Now, it is referred to as the “cradle of biodiversity,” boasting stunning views and an ecosystem that includes over 200 species—making it a true national treasure. However, today more than ever, the lake is threatened by the desire of businesses to seize as much territory as possible, jeopardizing its “protected” status. Activists and local citizens are raising their voices in concern over the chaos caused by the economic interests of certain parties before it is too late.

For several years, the non-governmental organizations that take care of the preservation of the Ohrid region have been sounding the alarm that buildings, hotels and cafes are being illegally built in the protected area around the lake. The permits without studies given by respective municipalities are threatening the heritage of Lake Ohrid.

“The lake has lost its beauty due to numerous concrete buildings and beautiful hotels that discharge wastewater into the divine beauty of the lake. The narrow sidewalks and the lack of an Effective General Management Plan for the lake are creating a chaotic situation. Authorities meet whenever there is a project, but they are not working every day because the situation is filled with daily problems for both countries,” says Stela Ahmeti, an environmental expert from the NGO “Friends of the Environment” in Pogradec.

Corruption and the arbitrary decisions of certain powerful local figures are taking place on both sides of Lake Ohrid. The city of Ohrid has only one construction inspector for the whole city, which is a very big problem to deal with all of the (400 for now) illegal buildings around the lake. In 2019, the Albanian side of lake was declared a protected World Heritage site for the first time, and the other part (Macedonian), which was protected as natural (1979) and cultural heritage (1980) was debated by UNESCO to be included in the list of endangered world heritage sites.

Local governments are turning a blind eye towards informal buildings, legalised in contravention of relevant laws and often connected to municipality councilors. Most interesting is that at the height of UNESCO’s warning against demolishing illegal buildings, a municipal councilor built a pizzeria within the protected area, accompanied by the mayor of Struga (a city next to Ohrid).

In Albania, companies related to politicians have built hotel complexes, which dump their waste into the lake and conduct illegal fishing activity, selling it on the market. Lake Ohrid is facing many challenges such as the lack of a regional plan of management, discordance of cross-bordering cooperation, and unwillingness from the local governments to change this, because of their personal benefit.

Photos of informal constructions around Lake Ohrid, showcasing the environmental risks they pose to this UNESCO World Heritage site. Photos: Costanza Musto

Power and Accountability: High Officials in Jail on Both Sides of Lake Ohrid

Court Sentences Former Mayor of Pogradec to 1.6 Years in Prison for Abuse of Power

Eduart Kapri, the former Democratic mayor of Pogradec, was found guilty of “Abuse of Power” in collaboration with others and sentenced to one year and six months in prison. The court ordered a suspension of the execution of the sentence and placed the former local official on probation for two years. Additionally, the court revoked his right to hold public office for five years.

Alongside Kapri, two other former officials, Besmira Niko and Besjan Meço, received sentences of one year and four months probation and a five-year ban from holding public office for their roles in the same case. According to the Special Prosecution Against Corruption and Organized Crime (SPAK), Kapri, with the assistance of the two officials, allowed the Gedi sh.p.k. company to resume suspended construction work on a twelve-story building. The former mayor had previously served as the administrator of the company in question, transferring ownership to his brother when he assumed public office.

Status Quo on the North Macedonian Side of Lake Ohrid: Ongoing Challenges Despite UNESCO Oversight

Over a year has passed since UNESCO granted the Macedonian side of Lake Ohrid a reprieve from being listed as an endangered world heritage site, while the Albanian side was officially recognized. Despite this opportunity, little has visibly changed on the ground. An ongoing assessment of the environmental and cultural impacts of illegal construction is being conducted, but local activists argue that municipal actions are creating an illusion of progress while potentially worsening the situation.

Recent reports indicate that the Municipality of Ohrid has recorded 15,700 requests for legal status concerning 19,624 facilities, with only 5,645 applications approved and 2,432 rejected. Alarmingly, 11,536 objects remain in the process of obtaining legal status, with 414 of these located within a 50-meter coastal strip of Lake Ohrid.

Despite promises from local officials for improved management, illegal constructions continue to proliferate, often sanctioned by powerful local figures. Controversially, the Mayor of Struga, Ramiz Merko, has publicly stated that he has no intention of demolishing illegal buildings, believing instead that the city should focus on tourism development. This stance raises concerns, especially as some of these illegal constructions are associated with influential political members.

Activist Dragana Velkovska from Ohrid SOS remarked, “This situation creates the illusion that greater care is being taken for the Ohrid Region while, in fact, even greater chaos is being created, framed in plans.”

The much-anticipated Ohrid Region Management Plan, which aims to address these challenges, was only adopted this year after a decade-long delay. Localized issues, such as a shortage of construction inspectors—previously only one inspector managed the area—remain significant barriers.

As the public awaits decisive actions that align with UNESCO’s recommendations, the collective calls from NGOs like Ohrid SOS highlight the urgent need for transparency and accountability among officials. Velkovska emphasizes, “You can only imagine how strong motivation is needed to continuously monitor the work of Macedonian institutions. Citizens are increasingly turning to us for help to address these injustices.”

Ultimately, the intertwining of political interests and systemic corruption threatens the preservation of Lake Ohrid’s unique cultural and environmental heritage, underscoring the need for united efforts from local, national, and international stakeholders.

UNESCO Report Raises Alarm: Lake Ohrid at a Critical Juncture

In early 2024, the UNESCO World Heritage Center published a 125-page report following a reactive monitoring mission in the Ohrid region, detailing significant irregularities in the care and protection of Lake Ohrid in both North Macedonia and Albania. The report reiterated urgent calls for both countries to implement dozens of recommendations, including the demolition of illegally constructed buildings and strict adherence to a building moratorium along the lake’s shores. UNESCO highlighted the continuous degradation of the region’s cultural and natural heritage, recommending that Lake Ohrid be placed on the endangered heritage list due to ongoing threats.

Despite efforts, the actions taken to remove illegal constructions have been slow, particularly in North Macedonia. The report emphasized that while the documentation of illegal structures represents progress, the actual demolition of these buildings is lagging far behind. Notably, 414 illegal structures have been recorded within 50 meters of the lake’s shoreline, with 2,321 illegal buildings documented in the nearby Galichica National Park.

Local activist group Ohrid SOS expressed their deep concern, stating, “Over the past four years, progress has been a step forward and three steps back, with very few effective demolitions of illegal constructions.” They condemned what they view as systematic neglect by authorities, accusing them of prioritizing corrupt interests over environmental protection.

In light of the alarming findings, discussions among government officials focused on addressing these issues, emphasizing the urgent need for coordination among all stakeholders to eliminate risks threatening the lake. The government announced initiatives aimed at the prompt demolition of illegal structures, stressing that measures must be taken to restore the area’s unique ecological balance.

Despite promises of action, the reality on the ground reveals ongoing challenges, as new illegal developments continue to emerge even as authorities initiate demolitions. Local NGOs and community members call for immediate and effective responses, warning that without stringent enforcement and accountability, Lake Ohrid could soon reach a point of no return.

Lake Ohrid Under Siege: The Threat of Pollution and Neglected Conservation Efforts

Pollution poses a significant threat to Lake Ohrid’s fragile ecosystem and its UNESCO World Heritage status. Despite being one of Europe’s oldest and most biodiverse lakes, home to nearly 300 endemic species, the region has become increasingly compromised by environmental degradation. Thousands of tons of mining waste are still present along the shoreline and in the surrounding hills, remnants of past exploitation and ongoing concession contracts. Environmental expert Arjan Merolli highlighted the severity of the situation, stating, “If we do not take immediate measures to address these mining wastes, which are highly dangerous, we risk losing the criteria for which this region was designated as a world natural heritage.” He pointed out that heavy metals are now found in commercially significant fish species, with pollution levels exceeding European Union standards.

During a UNESCO monitoring mission, it was recommended that mining activities be halted and the existing waste sites, including the mining dumps along the lake, be urgently rehabilitated to mitigate environmental impacts. Local authorities have been criticized for their slow response to these recommendations. Gani Bego, a specialist in protected area administration, noted, “Although some mining operations have diminished, several companies still conduct activities that pose risks to water quality, and metals from these activities can easily enter the lake through rainfall runoff.” Local NGOs, like Ohrid SOS, have condemned the inaction, asserting that systematic neglect by authorities prioritizes short-term profits over long-term sustainability.

Recent plans have emerged, including the “Ohrid Region Management Plan” (2020-2029), which aims to enhance cooperation between local governments and implement conservation measures, but actual on-the-ground improvements remain slow and inconsistent. As new illegal buildings continue to threaten the ecological balance, there is a growing urgency for concrete actions—such as immediate demolition of illegal constructions, stricter enforcement of environmental regulations, and the establishment of effective monitoring mechanisms—to secure Lake Ohrid’s future. Without these measures, experts warn that the lake could lose its UNESCO designation, reflecting further deterioration of its unique natural and cultural significance.

Lack of a bilateral agreement for the protection of Lake Ohrid

Currently, there is no agreement between Albania and North Macedonia to protect Lake Ohrid. Arian Meroli, a researcher from Pogradec with 25 years of experience studying the lake, states that the first bilateral agreement was signed in 1996. A subsequent agreement was ratified in 2005 and remained valid until 2013. However, efforts to reach a new agreement in 2019 failed.

Merolli points out a lack of motivation among authorities in both countries to address issues threatening one of the world’s oldest lakes.

He explains that cooperation began in 1996 when the international community convened both nations to find a sustainable solution for the lake’s preservation. The initial agreement, signed in October 1996, was supported by a grant from the World Bank for the Lake Ohrid Preservation Project. This established a framework for cooperation and led to another agreement ratified in February 2005 for the lake’s sustainable development.

One goal of this agreement was to create a bilateral structure with representatives from both governments and local authorities responsible for implementation. This structure was active until 2013, making significant decisions for the region. Unfortunately, these structures have not functioned since 2013, following an unsuccessful attempt to modify them in 2019, leading to a lack of real collaboration and will to resolve pressing issues for the lake’s ecosystem,” concluded Arian Meroli.

Visual evidence of the pollution impacting Lake Ohrid’s beauty and ecosystem. Photos: Costanza Musto

Businesses in the area generate impressive profits from tourism but invest nothing in environmental protection.

When you take a leisurely boat ride on the lake, you might see wastewater spilling into the lake, as shown in this photo. “This has not been seen anywhere in the world,” says Spiro, who is speaking off-camera from the tourist village of Drilon. “The hotels and restaurants, whose owners we don’t know, want to make more money but don’t invest in making the lake attractive outside their buildings. This is hurting our crops and creating health risks—it’s suffocating us.”

Hotel and restaurant owners in Pogradec are resisting a government regulation that requires them to install wastewater treatment plants. They argue that such an investment is burdensome for their budgets and unnecessary, as the city has a public facility capable of handling wastewater from private entities.

The estimated installation costs range from €13,000 to €100,000, which many business owners cannot afford. In total, 120 businesses in the municipality plan to appeal to the Ministry of Infrastructure to revoke this regulation specifically for Pogradec. They have also requested a halt to fines, which can reach up to 1 million Albanian Lekë, warning of potential protests if their demands are not met.

Spiro shares his worries: “I’ve watched the place I loved as a child turn into a dumping ground for black water from informal buildings. The hotels say they will bring prosperity, but they just bring pollution. I feel like I’m losing a piece of my childhood…”

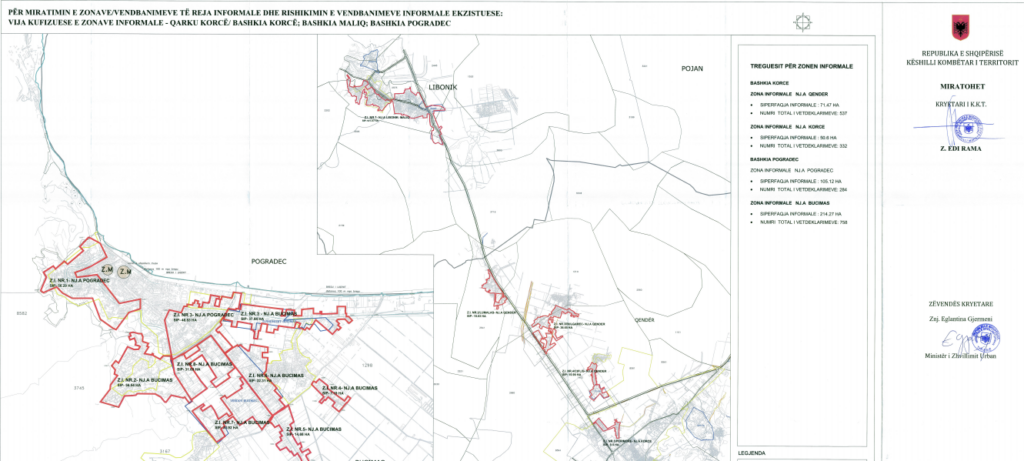

According to a recent report from the Albanian State Agency for Legalization, Urbanization, and Integration of Informal Buildings (ALUIZNI), about 105.2 hectares of land in Pogradec are occupied by informal constructions, mostly along the lake.

ALUIZNI report photo

Earlier this year, media reports raised concerns about pollution from these informal buildings, but the Ministry of Environment has not responded. These concerns led to several protests by residents in December 2024.

Pictures of abandoned construction sites in Lin, Albania—illustrating the lack of investment in environmental protection despite the significant profits generated by local tourism. Photos: Costanza Musto

“There are many things that need improvement, such as studying the boundaries of protected areas before granting construction permits around the lake. The decline in water quality and ecosystems, along with the inability to promote sustainable water use, does not help address floods and droughts,” says Syrja Berberi, an ecologist from Friends of the Environment in Pogradec, a local organization focused on citizen activism.

Other issues threatening the lake include fishing businesses and fish farming in the Drilon River area and the village of Tushemisht, which numbers around 17, mostly located along the riverbanks. These businesses threaten the unique plants and animals of the lake. Moreover, the water from fish farming adds waste to the lake, which disrupts local ecosystems.

It’s important to note that many of these fishing and farming operations do not have the proper licenses. In this area, construction is only allowed with the required permits, but most are not approved. This situation is accepted because all the rivers flowing into Lake Ohrid make the ecosystem vulnerable. An investigation revealed that there are 43 illegal businesses related to fishing and fish farming.

Some of these businesses use small fish from Lake Ohrid, caught by local fishermen, with amounts reaching hundreds of kilograms each day. This fish is used as food to replace fish feed. This practice is troubling because catching small fish disrupts the food chain in the lake.

Untreated wastewater from cities is a major source of pollution in the area. For many years, polluted water has been discharged into Lake Ohrid from Pogradec and nearby villages, negatively impacting the lake’s environment. Last year, a drainage canal was built to remove excess water, but now it also handles wastewater from Pogradec. This canal has helped assess the environmental impact of the water used in the area, but a proper global pollution index method is not yet used in the country.

The lake supports around 170,000 residents, sustaining economic activities such as fishing, agriculture, hydropower, and tourism. However, in recent years, the lake has faced numerous challenges, including a decline in fish reserves, eutrophication, habitat destruction, and poor water quality.

Up until September 28, 2020, there was no Cross-Border Management Plan for Lake Ohrid, but a draft for the Lake Ohrid Watershed Management Plan was finally created in line with the EU Water Framework Directive. This plan was presented at a national meeting organized by the Ministry of Environment of North Macedonia, attended by around 30 representatives from various ministries, public institutions, local government, civil society, and scientific communities in North Macedonia. This plan aims to enhance cooperation between Albania and North Macedonia in managing Lake Ohrid, which is a hot spot for biodiversity with over 300 endemic species.

However, even as this strategic draft has been proposed, concerns about who is actually protecting the lake remain.

Local activists have noted that the working groups from the municipalities on both sides of the cross-border lake have not met, only coming together during EU projects.

In a request for information directed to the Pogradec Municipality regarding their management plan for urban waste, as well as whether there is a registry of informal constructions along the lake, there has been no response from local authorities from January 2025 to the time of this publication.

Rural Women of Lake Ohrid Struggling Amidst Tourism Growth

The ongoing construction work has sparked not only worries about lost income but also concerns regarding environmental damage due to the use of materials like steel and iron. Locals feel defeated, expressing that these imposed changes are harming what was once a natural wonder. Criticism has been directed at the American-Albanian Development Foundation, which has faced allegations from the opposition regarding its controversial actions. Originally established by the U.S. Congress to increase strategic investments in the region, the foundation’s transformation into an NGO has raised questions about its interests and responsibilities.

As construction continues without a clear timeline for completion, women who have lost their income receive no form of compensation or support, leaving their futures uncertain as Drilon transforms before their eyes.

Ina Zhupa, a member of parliament for the opposition Democratic Party, criticized Prime Minister Edi Rama’s government in an interview with Portali Vizion, highlighting that the millions of tourists celebrated in newspaper headlines stem from a very specific political strategy. Zhupa stated, “The government’s estimates are not accurate. The claim of 10 million tourists is based on overall visitor numbers to the country. Most of these are not tourists but emigrants returning to visit family during the summer or residents of Kosovo spending a day in Albania.” Notably, media estimates indicate that approximately 3.8 million Kosovars visited Albania during the tourist season. “This means that, considering the population of Kosovo, every individual made two trips to Albania over the summer.”

These inflated figures have led to a surge in accommodation prices, causing further problems for sustainable tourism. The pressure on local businesses to accommodate this supposed influx of tourists has contributed to the rapid rise of illegal buildings that encroach upon the natural landscape of Lake Ohrid. As a result, the integrity of this UNESCO World Heritage site is being compromised, threatening both the environment and the very foundation of sustainable tourism that communities rely on. The focus on quantity over quality in tourism threatens to destroy the delicate balance necessary for the preservation of local culture and the ecosystem.

View of the reconstruction in Driloni, Pogradec, where local women are facing the loss of income from selling traditional products. Photos: Costanza Musto

Rural women from the touristic villages around Lake Ohrid are recognized as the pillars of local tourism and culinary arts, however, they face significant challenges. Maria, a local fish vendor from Pogradec, has been deeply affected by this situation. ‘‘I used to catch plenty of fish that were healthy and abundant. Now, I am worried every time I sell my catch,’’ she says. ‘‘The lake that gave us our livelihood is now being polluted, and I feel helpless.’’

The rise of fancy hotels and informal buildings has diminished their opportunities to sell their products, leaving them without a space to showcase their crafts and local goods. Despite their vital contributions as hosts and producers, many of these women have limited knowledge of their rights and receive little institutional support for skills development.

At a recent summit, 90 women and girls from the villages around Lake Ohrid gathered to discuss their roles in social, economic, and tourism development. The lack of infrastructure and proper opportunities underscores the urgent need to invest in rural women to ensure sustainable development in the Ohrid region. Informal buildings and unregulated tourism growth threaten not only the environmental integrity of the lake but also the livelihoods of these women who rely on the natural beauty of the area.

The Albanian Network for Rural Development states in their declaration, “To our stakeholders, empowering rural women is not just an investment in individuals, but in the entire community’s resilience and sustainable future.” While these women significantly contribute to the tourism and agricultural sectors, their ongoing challenges—including low pensions, unemployment, and limited social mobility—highlight the critical need for their voices to be heard and their contributions recognized. Only by addressing these issues and empowering rural women can we secure a thriving future for both the community and the cherished heritage of Lake Ohrid.

This research has been supported by the European Fund for the Balkans within the Engaged Democracy Initiative